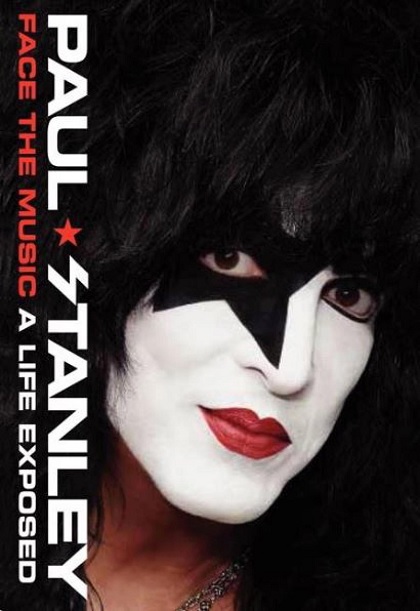

Book

KISS SINGER PAUL STANLEY FACES THE MUSIC IN CANDID AUTOBIOGRAPHY

By Peter Roche / Cleveland Music Examiner

“I needed to reflect personally,” says the rocker in Face the Music, available now from Harper-Collins. “But also to let fans see themselves in it, and see where my story might take them.”

More specifically, Stanley—a teenage reject turned millionaire music icon—wanted to let troubled readers know it’s still possible to conquer dysfunctional upbringing, physical deformity, and assorted personality quirks when chasing one’s dreams.

Unlike recent autobiographies by fellow KISS alum Ace Frehley (No Regrets) and Peter Criss (Makeup to Breakup: My Life in and Out of KISS), Stanley’s tome is devoid all those now-cliché celebrity struggles with substance abuse and revolving-door rehab stints. Instead, the man known as Starchild basis his life story on the psychological impact of having (and overcoming) a partially-formed ear.

Indeed, the book’s intro brings us backstage minutes before a 2013 concert, where the KISS singer talks his way through the makeup application process that—for forty-years—has transformed him into the familiar, can-do superstar behind some of rock’s greatest hits.

Stanley admits early on that he always regarded his Starchild alter-ego as much more than one of the band’s clown-faced musical superheroes. Teased throughout his childhood in Manhattan (and Queens), New York for his Jewish heritage and ear-warping microtia, the man born Stanley Harvey Eisen slipped into the persona and willingly basked in the security it afforded. In the course of a few short years, Stanley went from chubby loser nobody wanted to focal point in one of most successful rock bands ever—a dashing, desirable songsmith with more wealth and fame than he could’ve fathomed as an awkward pre-teen in PS-98 school.

The guitarist dishes on his turbulent boyhood, overbearing mother, and secretive father, and opens up about troubled sister, Julia, whose mental illness lead to substance abuse and teenage pregnancy. Stanley turned to music for escape, reveling in the sounds of Jerry Lee Lewis, Eddie Cochran, Little Richard, and the popular doo-wop groups of the day. But it was The Beatles’ legendary appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show that inspired the loner to take up songwriting as a hobby (and career): “I can do that!” He tinkered on the acoustic guitar he received as a gift at age thirteen, but didn’t devote himself to the instrument until he acquired an electric.

Stanley displayed an aptitude for visual arts—a skill that would serve him well later—and excelled at New York’s High School of Music and Art at the onset of the 1970’s. He dabbled in various bands during this time, finding early success in Rainbow (not to be confused with the Ronnie James Dio band). Finding a kindred spirit in Israeli-born chum Chaim Witz—aka Gene Simmons—Stanley turned his attention to writing original music instead of merely banging out covers. The earliest incarnation of KISS (then known as Wicked Lester) recorded an album but couldn’t secure a record deal, so Stanley and Simmons threw themselves into their live performances. Magazine ads placed for a drummer and lead guitarist resulted in the recruitment of Peter Criss and Ace Frehley, who showed up for his audition in mismatched sneakers.

The meat of the memoirs sees the Starchild recounting his early days steering the KISS machine with business-minded bassist Simmons. Toying with the makeup favored by glam artists like David Bowie and theatrical stage shows offered by shock-rockers like Alice Cooper, the KISS men put on the face-paint and premiered their now-famous alter-egos (Starchild, Demon, Space Ace, and Cat Man) to fascinated audiences in the Midwest. Stanley is quick to admit, however, that the crowds were initially small and had to be cultivated with each new showcase. Before long, the hard-charging band won the attention of TV promoter Bill Aucoin (Flipside), who inked a deal with Neil Bogart’s fledgling Casablanca record label.

Stanley concedes the group’s first few albums (KISS, Hotter Than Hell, and Dressed to Kill) sounded anemic compared with their mind-blowing concerts, so they hired Jimi Hendrix producer Eddie Kramer to helm a live record that captured the energy onstage and did justice to neck-breaking hits like “Strutter,” “Cold Gin,” “Firehouse,” “Deuce,” “Parasite,” and “Rock and Roll All Nite.” Stanley acknowledges that Kramer and his engineers “doctored” the Detroit recordings, adding the audience noise and ambiance that wasn’t picked up by the mixing board at Cobo Hall. The resulting double-disc, KISS: Alive, propelled the band into the stratosphere.

Stanley takes readers backstage and behind-the-scenes on tour buses and hotel rooms, where the debauchery and drug use (by Criss and Frehley, anyway) reached epic proportions. As Starchild, he had his pick of women, but his promiscuity only exacerbated an inner loneliness. As his wealth increased, he took note of the disparity between socioeconomic classes and sometimes became uncomfortable with the attention lavished upon when recognized by salespeople. At a jewelry store, he teaches a clerk not to judge based on outward appearances. At a local music equipment retailer he turns down free goods, telling the employee to give the gear to a musician who can’t afford it.

KISS becomes more popular with each new album (Destroyer, Rock and Roll Over, Love Gun), but their egos are tempered by producer Bob Ezrin (“Don’t ever stop playing unless I tell you!”) and their accountants, who glumly report that they’re barely breaking even—despite all the cash trading hands. Stanley reveals that the band’s early tours were financed by Bogart’s American Express card, and that the mogul often funneled KISS profits to other Casablanca artists. The backroom shenanigans ultimately lead to the band’s split with their once-benevolent manager and his increasingly disco-centric label.

Although KISS was voted the world’s most popular band in a 1977 Gallop Poll, Stanley and Simmons sensed that the tide had shifted by the end of the ‘70s: Their marketing strategies had worked too well, drawing youngsters to the KISS camp and earning the ire of long-time fans who cried “sellout.” A quartet of simultaneously-issued solo albums sold well, but not nearly as well as expected, resulting in massive returns. And the embarrassing made-for-TV movie “KISS Meets The Phantom of the Park” only provided detractors with additional ammunition. Stanley notes that Simmons became distracted with outside interests (like film and music production), leaving him to steer the ship alone. Frehley’s behavior worsened with his drinking and drug use until the guitarist became flat-out unreliable. Criss’ shortcomings behind the drum kit became apparent after he was replaced (following a car accident) by Anton Fig.

Soon enough, both Space Ace and Cat Man were ejected from the band, with Vinnie Vincent and Bruce Kulick filling in on guitar in the ‘80s and Eric Carr handling percussion on albums like Creatures of the Night, Lick It Up, Animalize, and Asylum. Stanley recounts how the group determined to go “unmasked” for the MTV age, appearing in public for the first time sans makeup on the nascent video channel in 1983—and how the line between his public image and private persona became increasingly blurred without the Starchild guise. Even after undergoing surgery to correct his deformed ear, Stanley gets the sense that there’s two—even three—distinct personalities at play: The Starchild, unmasked rock star Paul Stanley, and the still-shy (if far more confident) Paul Stanley, regular guy.

Later chapters take us through KISS’s rebirths and reformations, starting with an MTV Unplugged appearance in the mid-1990s. Stanley recalls how the event—which featured guest appearances by Frehley and Criss—prompted a full-blown reunion tour and studio album (Psycho Circus), and how fan-fronted conventions sparked a return to the makeup of old. The guitarist and drummer get up to their old tricks (and a few new ones), however, frustrating Stanley and Simmons even as the money poured in. Stanley finds catharsis in painting and acting (in a Canadian production of Phantom of The Opera) and unexpected solace in marriage and fatherhood, and the several vignettes featuring Paul cooking or clowning around with his kids rank amongst the book’s most touching moments.

Preview the book here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=XP3W0renQec

As the ‘90s become the naughties, KISS soldiered on with Singer on drums and ex-roadie Tommy Thayer on guitar, alienating some old-school enthusiasts. Stanley defends their places in the band, however, arguing that Frehley and Criss squandered their talents and failed to capitalize on the second chance offered by the reunions. The singer describes the KISS characters as superheroes (like Batman)—any one of whom (himself included) could be replaced by surrogates in the name of show business—and explains his (and Gene’s) reasons for wanting to protect not only KISS the band, but KISS the brand.

The book may not divulge much of anything diehard KISS fans don’t already know. But it’s in Stanley’s telling of his own story (with an assist from journalist / translator Tim Mohr) that readers get a true sense of the triumphs and trappings of rock celebrity—or what fellow rockers Rush once described as the “glittering prizes and endless compromises” of stardom. What emerges is the portrait of a talented sexagenarian who remains remarkably well-grounded and humble despite a lifetime of unfathomable commercial and artistic success. But the Starchild lets down his guard, too: Stanley owns his mistakes, apologizes for some hot-headedness, and professes a love for all his KISS brethren and the army of fans who catapulted them to fame (and induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame). The high-heeled hero insists other people from all walks of life can make their dreams become reality, too—if they’re as willing to work for it.

“Is the book tough on some people?” ponders the author. “Yeah, but it’s also tough on me. And if telling my tale can offer a glimmer of hope to someone, then it was all worth it.”

To that end, Stanley’s Face the Music: A Life Exposed stands as the KISS bio to beat.